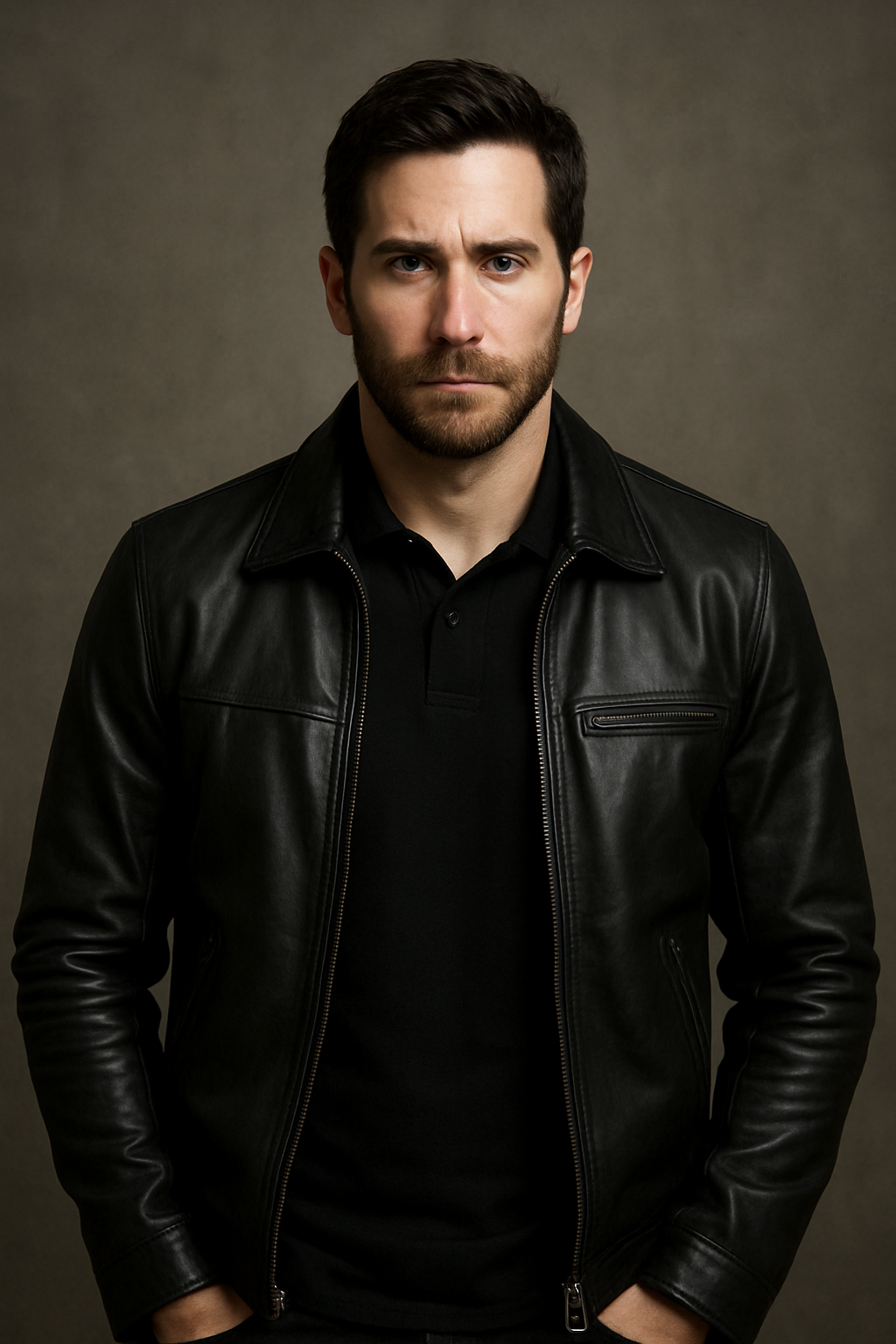

George

My name’s George Merrick. My life used to be more straightforward. I’m British, early thirties, married but no children. I was a fraud prevention analyst for a bank and wore a suit every day which suited me. It meant I never had to obsess over what I was going to wear. I turned up to work on time every day, and I almost always went home late.

I was good at my job. Perhaps, too good.

Give me ten thousand lines of transaction data and I could tell you which three needed looking at.

Give me a face-to-face conversation and I was lost after about thirty seconds.

Numbers make sense, people don’t. I learnt at a young that if I kept my face still and my voice flat, most people would leave me alone. Colleagues still called me intense, odd, and a bit much. There were the occasional HR conversations about “communication style” and “emotional impact”. I spent more evenings than I like to admit replaying the same meetings in my head, trying to work out exactly which sentence I had got wrong this time. I was never trying to be rude. I just thought the point of a meeting was to fix the problem, not dance around it.

Then one night during what should have been a routine traffic stop, a gun was pulled from my car.

I learnt young that if I kept my face still and my voice flat, most people would leave me alone. Colleagues called me intense, odd, a bit much. There were HR conversations about “communication style” and “emotional impact”. I spent more evenings than I like to admit replaying the same meetings in my head, trying to work out exactly which sentence I had got wrong this time. I was never trying to be rude. I just thought the point of a meeting was to fix the problem, not dance around it.

My entire life stopped being about spreadsheets. I went down for possession and was given a five year custodial sentence. I knew it wasn’t my gun but the court didn’t care. The system is much more comfortable with simple stories. Man. Car. Weapon. Tick.

Prison strips everything away that is not essential. Your clothes, your job title, the stories you told yourself about being one of the good ones. They give you a number, a grey tracksuit and a door that locks from the outside. At first, I reacted badly. I was obsessed with the injustice and that’s all I could think about day and night. That’s my head, always so loud on the inside, silent on the outside.

Eventually I learned to adapt.

I watched. I counted. I mapped the place in my head because it was easier than thinking about what I had lost.

That’s when I met Polish. He’ll probably have told you his version already. From my side it was simple. I needed a cellmate who wouldn’t stab me in my sleep. He had a reputation for being dangerous, but it was the kind of dangerous that made sense to me. Quick temper, clear lines, his violence pointed at people who hurt others. He traded fairly. He kept his word. In here that put him in the top one per cent.

Sharing a cell with Polish taught me two things. The first was that someone can be covered in labels like “violent offender” and still be the person who pulls you back from stupid choices. The second was that once you have seen the roots of someone’s rage, it is very hard to sit in judgement over the branches.

I would like to say I adapted quickly, but that would be a lie. I spent a lot of time afraid, and when I was not afraid I was furious. Furious at the police who ignored the context, at the court that did not listen, at myself for not spotting what was coming. There were moments when it would have been very easy to become exactly what the paperwork said I was.

What stopped me tipping over the edge completely was the same thing that put me in there in the first place. Pattern recognition. Once I calmed down enough to look, really look, I started to see the lines that joined things. How contraband moved. How certain officers looked the other way for certain people.

I began to understand something I had never wanted to contemplate. The problem was bigger than my case. Bigger than one bad night and one bad decision.

There were people out there hurting kids.

When I eventually walk out of those gates I’ll have a sense of obligation to put a stop to this.

Which brings me to Natalia and Adel.

When I first met them, I felt like a stray dog that had somehow wandered into the wrong house. Natalia insists on seeing the good in people. She works all hours running five small shops in Stratford, then still finds time to sit on cold pavements handing out food packs to people everyone else pretends not to see.

Adel’s sixteen, louder than the rest of the world put together, and has a brain that moves so fast it makes most people tired just watching her.

They should both have taken one look at me and stayed well clear.

They didn’t.

Natalia looked past the record, the temper and the discomfort and saw something in me I had never managed to see in myself. Not “a project”, not a lost cause, just someone who was tired and didn’t know where to put his anger. She has this way of de-escalating things without making you feel like a child. A hand on my arm at the right time, a quiet word in the kitchen, a plate of food pushed in front of me before I realise I am hungry. She does it with Adel too. I recognised the pattern. The difference is I never had anyone do it for me before.

Adel calls me the stray her mum adopted.

She’s relentless, honest to the point of being surgical, and every so often she says something that cuts straight through the noise in my head and lands exactly where it needs to. I have met a lot of people who say they want the world to be better. Adel actually cannot function if it is not. There is a difference.

Around them I’m still me. I still do not always know what to say. I still get it wrong. I still replay conversations at night and wish I had picked a different sentence. The difference now is that when I make a mistake, it is not the end of the world. We talk. We adjust. We try again. That is new. That matters.

I’m not going to pretend meeting them magically fixed anything. It did something stranger. It shifted the cost of failure. Before, if I went too far or ended up back in a cell, it was my problem. Now it is not just my problem. There is a woman who finally laughs with her whole face and a girl whose head finally goes quiet sometimes when she is climbing or flying off a beam, and I am part of the reason they feel safe enough to do that. That changes how you weigh risk.

What do I want now.

On the surface, simple things. I want to sit in Natalia’s kitchen with a mug of coffee that does not taste of prison, listening to Adel swear at some drama on TV. I want to walk through Stratford and not flinch every time I see a police car. I want to earn enough that I can pay for my own meals without feeling like a charity case. I want to be someone Adel can be proud to introduce, not “this bloke my mum is helping out”.

Underneath that, there is something else. The same thing that kept me awake in my cell on Anglia wing, staring at cracks in the ceiling. There are people out there who build their lives on the backs of those who cannot fight back, who look at children and see product, who look at addiction and see opportunity. I have seen enough of that now to know that if I walk away and pretend I did not, I am no better than they are.

I am someone who is very good at following the money and very bad at leaving things alone once I know where the trail leads. That is dangerous. It is also useful.

So that is me. George Merrick. Spreadsheet addict, social liability, ex con, reluctant stray, and the last person you want paying attention if you are hurting people and think no one is joining the dots. I did not choose what happened to me, but I can choose what I do with it. And I intend to do something that makes the cost worthwhile.